Interviewed by Deepa Punjani*

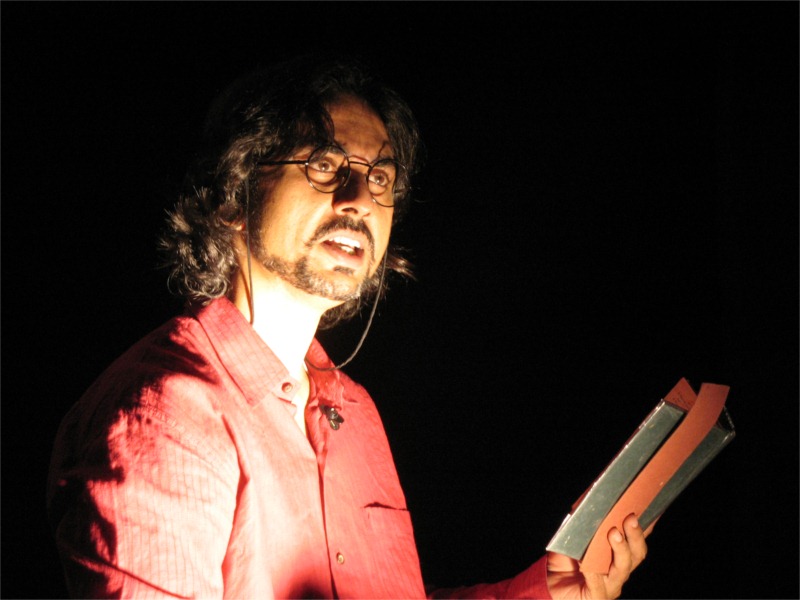

Ramu Ramanathan is an Indian playwright-director with acclaimed plays to his credit. His latest play Comrade Kumbhakarna has been produced by the National School of Drama’s Repertory, and is touring all-over India. Ramanathan’s work bears an urbane testimony to a country that has never been quite easy to decipher. Here is a writer who has transformed social and political commentary through the multi-layered tapestry of performance. A collection of eight of his plays, 3 Sakina Manzil and Other Plays, will be published by the English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, and by Orient Blackswan. Informed, incisive, ironical, Ramanathan’s work is reminiscent of the great tradition of the Enlightenment.

1. Is there any major issue that you feel artistes in India fail or neglect to address on stage? Why?

India is a caste-driven society. What is worrying is, India has become a theatre of the upper-caste. If you scratch the surface, the directors, the playwrights, the critics, are all upper-caste. I think it’s very exclusivist, elitist and camp-ish.

Is this due to censorship, or to a blind spot in the community’s shared perception of the world? — or to a community’s consciously or un-consciously avoiding it?

If you consider the 150 tamasha (popular folk theatre form; a people’s theatre) companies in Maharashtra, you understand why. For one, tamasha is not considered art. Why so? I’ve always wondered who benchmarks what is high art or not so high…. Then there are the day-to-day issues of tamasha. Who pays to the wealthy sahukaars (money lenders) or for the chirimiri (bribe)? Who pays for the diesel; who pays for the car? Who pays for the taxes, and the exploitative licensing? Whatever remains is for government bribes. Today, the state subsidies have vanished. How can we sustain a co-operative theatre movement which involves thousands of low-caste artistes being crushed by our own government and the higher castes?

2. What, if anything, is difficult in communicating with the designers/directors/actors/playwrights? Why?

I think most of us know what we want to say on the stage. The big issue is how to say it. Google is making us stupid. They say, there are 107 trillion emails being sent in a year. That’s a bit numbing. The technology is evolving, and one can get carried away by it. Ultimately, it is the consumption of the content that makes the revolution. Atoms we are, and to atoms we shall return. To convince theatre audiences and theatre practitioners of the potency of the written word is tough.

How early and how often do you exchange views about the coming production?

We try to work in tandem all the time. For example in Mahadevbhai, Jaimini Pathak and I rehearsed on an open terrace. It’s really tedious rehearsing a one-person play. There’s the actor and there’s you. That’s it. And the actor is desperately hanging onto you for dear life. We were workshopping all kinds of staging options, when one day, I noticed the terrace flooring. It was made up of Chinese mosaic tiles. Now, most Mumbai buildings have a water-leakage problem, and so, the terrace flooring had patterns to seal the gaps. Coincidentally Jaimini was moving in and out of these patterns. That became my stage design. We kept things simple, spartan and Gandhian.

3. In your creative process, which part do you enjoy least?

The absence of space in Mumbai is a big pain. Space is power. Space provides the equity which you can encash into productions and shows. Which is why I used to workshop in colleges in Mumbai so that I got space to rehearse, a space to perform and an audience. In the past, Mumbai provided the space. Occasionally! Now it doesn’t.

Religion sells. Art doesn’t. This is what Shahir Shanker Bhate told me recently. He is not a well known Shahir (an honorary title for a balladeer in Maharashtra); so he has been sitting at home. A former mill worker, Shahir Bhate has a huge reservoir of songs. His brain is the Wikipedia of Shahirs, songs, and their sagas. When he’s gone, all shall vanish. There’s no hard disk which will back-up the data. There’s no space which welcomes Shahir Bhate.

4. During your career, have you ever received a particularly insightful piece of criticism? When, and what did it say? What made it especially important for you?

The Boy Who Stopped Smiling had approximately 150 shows. In a way, I was attached to the play and traveled with it. At one point, Vijay Tendulkar told me, to stop doing so. He said: Your job is to write. The play is no longer yours. Learn to let go. It was a good tip. I was able to move on and write many more plays.

5. You are regarded as one of the most politically conscious playwrights of our generation. Yet each of your plays has been different, and these have reflected the times we live in. How would you describe your own work?

“Political” is a tag that I’ve inherited. Most of my friends are journalists, activists, lawyers, doctors. They are amused when they hear this. The powers that be are clever. The Andhra Pradesh Government may arrest Gaddar, Varavara Rao and Kalyan Rao in full public glare[1], but for most parts, the forces of intolerance prefer to co-opt the author. It’s easier, and no one protests.

I wrote a blog about this. Most of my colleagues in theatre believed that I shouldn’t have said what I did. That a true artiste should not get mixed up with politics. I totally disagree. I believe art and politics can never be separated. You can’t separate art and politics, because politics is life. It’s also a fact that life is political, and art is about life, so it is inevitable that art should be political.

In India, the bigger issue is about the nature of complicity in an artist. That is, what constitutes complicity? Is it one’s responsibility always to act out against a tyrannical regime or to, in perhaps more subtle ways, to beat the system?

That’s what one tries to do.

6. You are known to meticulously research your subject. Historical processes are the cornerstone of a lot of your writing, and both politics and history together form the foundation of your work. Can you tell us a little about your creative process as a writer?

I enjoy researching. I’m a bit shy. Research provides me the sanctity to step outside my comfort zone and meet people. For every play, I’ve had mentors who guide me. I meet people and spend time with them. This process began in my school years where I would live life in wonderment.

I used to pass a man who would walk on his hands on the streets. Who was this man? I constructed mythologies around him. I never found the truth. Another person was a waiter who served me my first beer in my eighth grade at Otter’s Club. He would inhale cigarette smoke and exhale it from his ears. I never figured out how he could do it.

Likewise in school, we had the actor Salman Khan, and another colleague in class called Richard who did bike tricks. Salman Khan did wheelies on branded bikes while Richard did it on a second-hand Yezdi. We cheered Richard. He was our hero. Recently, I met Richard. He runs a decrepit garage. He was embarrassed to shake hands with me. He felt he had fallen from grace. That he was no longer the hero.

Today Salman Khan is the Bollywood super-star. Again a residue from our past. Unfortunately, the past is ugly and unpleasant and diseased. But for me Richard remains a hero. He fought reality. That’s always tougher. I’ve retained this process of enquiry in my plays.

7. In your latest play, Comrade Kumbhakarna, you have created an anti-hero: a victim of the excesses of our Indian State. He questions the very foundations of our democracy: a familiar theme in your earlier work, too. What was the starting point for this play?

Arun Ferreira, Murali Ashok Reddy, Dharmendra Sriram Bhurle, Naresh Babulal Bansode were arrested on May 8, 2007 from Dikshabhoomi, Nagpur.[2] Later Arun and Murali underwent numerous rounds of torture and have been subject to narco-analysis tests.

Likewise, Vernon Gonsalves and Shridhar Shrinivas[3] were arrested from Mumbai on August 19, 2011 by the anti-terrorist Squad and were accused of being found with explosives. A short while ago, Sudhir Dhawale was arrested.[4] The list is endless. The point is, police custody, brutal torture and public apathy.

Comrade Kumbhakarna is a response to the blatant misuse of state power. I am wary of signing petitions. There was a time I attended meetings and hearings. I used to love to participate in rallies (nothing can be more invigorating than a protest rally), but the anti-establishment space has diminished in today’s India.

8. In Kashmir Kashmir, your earlier work, and now with Comrade Kumbhakarna, I sense an increasing disillusionment with the Indian State. Do you see hope, or do you think the capitulation of the State is complete in an India that has come to be increasingly concerned with its economic success more than anything else?

State power is the ultimate victor. There is a veneer of democracy. Kashmir is one end of the spectrum; the rest of India isn’t that far off. I did moot court hearings in a reputed law college. A moot court hearing is as real as a court room hearing…except instead of lawyers, it is enacted by students.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, we put on a moot court: the International Search for Justice. The idea was to try the world’s worst tyrants. And so, this moot court was about the Special Court of Sierra Leone, which has been set up jointly by the United Nations and Sierra Leonean government.

The four hours were a benumbing, and a shattering experience for me. In that class room, I heard about a little girl with no arms who said to her mother, “When will my arms grow, again?” Next to her was a baby suckling at his mother’s breast. Neither had arms. As one of the students pointed out, this is evil beyond belief.

After the moot court we held a post-mortem. The judge in chair congratulated the students for their impassioned plea for democracy, justice and the rule of law in Sierra Leone and Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The students were delighted.

Then the judge in chair asked the students their position about Assam and Bhagalapur and Godhra — about the perpetrators of riots in Delhi, Mumbai and Ahmedabad. About army action in Srinagar, Ghadchiroli and Imphal. There was an uncomfortable silence. Tomorrow’s lawyers and perhaps tomorrow’s judiciary had no answer.

My point is, we have been silenced into submission. It’s all skin-deep democracy.

9. In spite of all the sadness, your work also brims with humor and with the music and the cultural traditions of the people you are talking about. Your characters like Bhau and Kaka in Cotton 54 Polyester 86 or like the eponymous hero of Comrade Kumbhakarna are from marginalized communities representing their unique traditions. More than ever, these people find themselves living in situations of poverty (sometimes extreme) and deprivation. On the other hand, we tend to celebrate our “folk traditions” and their performers. How do you view this paradox?

Sometimes you sit and wonder if there is a point to creativity. Perhaps there should be a share price attached to it. Then it could be quantified. Like a million dollars for Bhimsen Joshi’s voice or a mukhdaby Birju Maharaj.[5]

10. A turning point in your career as a playwright was the play Mahadevbhai (1892—1942), which also turned out to be a very successful play. How do you see it today?

I attended a recent show on October 2, 2011, at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Mumbai. Six years ago, we had started a low-budget theatre festival on the campus, and it was amazing to see the students at IIT sustain the festival. It makes you happy. The actor Jaimini Pathak has performedMahadevbhai 250 times in the past decade. It’s an achievement. It requires serious stamina and determination.

I was watching a Mahadevbhai show after seven years, and I think, the play is important for what it says. There are three regrets though: I wish the first half of the first act was better written; I wish it was a bit more critical of the Indian National Congress movement; and above all, I wish I was able to explain better the position of Bhimrao Ambedkar, who was a founding father of independent India.[6] However Ambedkar would require another play. I believe, he is one of the greatest men this country has produced …

© Courtesy of Ramu Ramanathan, 2002

11. You have not only written plays with an immediate thrust on our politics today but you have also written plays for children and young people such as The Boy Who Stopped Smiling and Medha and Zhoomibsh (Part I and II).

A lot of children writing in India is cute. I took my cue from Rilke, who said children are innocent but above all, they are cruel.

12. You are also one of those rare playwrights who have actually written very empowered women characters in plays such as Shakespeare and She. You have directed Marguerite Duras’s L’Amante Anglaise as well.

There’s a Marguerite Duras line: “Marriage is a hazardous activity. Especially for women.” I’ve seen this happen to innumerable women. I’ve been surrounded by strong, independent, very progressive women. It’s tough being a woman in India, but they haven’t let that deter them.

There’s another play concerning women that I am working on. Thanks to Kinnari Vohra (the lady who consented to marry me) I have been led to the Mathura Rape Case. Owing to a progressive judgment and a nationwide women’s movement, the rape law was amended in 1983. Cruelty against women was made a crime in 1984. In 1986, the offence of dowry death was introduced.

The crux of the play is the rape of Mathura and the Supreme Court judgment in the Mathura rape case which was so regressive that it triggered off a nationwide movement. This is modern India’s history, which we have conveniently forgotten.

© Kavi Bhansali, 2005

© Kavi Bhansali, 2005

13. In plays like Collaborators and Shakespeare and She, which you have directed too, you have attempted different styles of performance. How did you arrive at these?

The brief for Collaborators was simple: Modern India died at 6.29 pm in a skyscraper in Mumbai. The composer Krishnan Anantha curated a sublime music score for the play. That set the tone for the production, the acting, the set and the overall aesthetics. We created futuristic furniture out of industrial waste. As the actors pointed out, this furniture is cruelly uncomfortable. That was true. But everyone knew we were trying to challenge the rulebook. Today the irony is, some of that furniture has gone mainstream.

In that sense Shakespeare and She was simpler and more minimal.

14. You have finally managed to overcome the questions concerning the identity of an Indian writer writing in English about a multicultural India brimming with diversity in all aspects of life. Your work is uniquely Indian and yet has a thoroughly modern sensibility to it. But for plays like Cotton 54 Polyester 86 and Comrade Kumbhakarna, you have felt it better for them to be translated and presented in Hindi. When this essential conundrum of language arises, how do you cope with it?

I accept it. I write in English which I know a bit better than the other languages. My problem is with the Hindi translators; they lag behind the other languages.

15. The city of Mumbai has been your inspiration for plays like 3 Sakina Manzil, Jazz and others…

3 Sakina Manzil was composed thanks to the inputs from Amrit Gangar. He played Virgil to my Dante. I visited Dongri, Keshav Naik Marg, Chinch Bunder (districts in Mumbai which were gravely impacted by the April 14, 1994 blast) with Amrit bhai.[7] Later, in the middle of the night, I stood in front of a building which burnt on April 14, 1944. I tried to relive those moments. It taught me empathy. Later, when the play was staged, I heard of audiences in Mumbai who saw the play and then they went off in search of 3 Sakina Manzil. They never found it, because the building is in my head. But they returned and said, it’s still the same. That’s true. The jharokhas (an old-world architectural design of balconies), the balcony, the Gujarat-Rajasthan style of architecture, little details on the shop front, the Kutchi traders.[8] And that makes you think that was so much more one could have done, if not for this ridiculous obsession with staging two hour plays.

16. Mumbai is where you live, and where you write. How do you see your relationship with Mumbai?

Mumbai is my lover. I love her and at the same time, I loathe her. To-date, even today, I discover something new in her. And that I’ve poured into the plays.

Endnotes

[1] Gaddar, whose actual name is Gummadi Vittal Rao, is a revolutionary balladeer and an activist. Along with Gaddar, Varavara Rao and Kalyan Rao are communists, activists, naxalite sympathizers (naxalite is a generic term used to represent the various militant communist groups in India), poets and anti-establishment speakers. Their political battles have been waged against the centralized government and their state governments in India, which they believe wrongly encourage feudalistic attitudes, imperialism (read globalization), and caste differences.

[2] Nagpur is a city in the state of Maharashtra. The Nagpur police arrested Arun Ferreira and his associates — Murali Ashok Reddy, Dharmendra Sriram Bhurle, Naresh Babulal Bansode — for alleged naxal related crimes. All of them have been subjected to third-degree torture by the police. Ferreira was freed when acquitted by the court, but the moment he set his foot outside the prison, he was arrested again on the pretext of two more cases.

[3] Vernon Gonsalves and Shreedhar Shrinivasan were also arrested for their suspected naxal activities.

[4] Sudhir Dhawale, a Dalit activist and editor of the Marathi magazine Vidrohi was arrested under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) by the Maharashtra state government. Formerly the untouchables of India, the Dalit belongs to the lowest caste under the caste system in India.

The Naxalite/Maoist situation in India is complex and has a bitter and unresolved history with the powers that came to be. In the past few years, activists have been routinely picked up by the state governments and put away as Naxals and Maoists. Similarly, acts such as the UAPA have been criticized for being draconian laws. State-induced terror is a reality in India and largely goes unchecked under the pretext of safety and governance. The powers in the central and the state governments of India are known to crush dissenting voices.

[5] Mukhdas are the introductory lines and also the main chorus lines in Hindustani classical music.

[6] Bhimrao Ambedkar was one of the founding fathers of independent India. He was the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution and leader of the Dalits.

[7] Amrit Gangar/Amrit bhai is the researcher and guide for the play 3 Sakina Manzil. ‘Bhai,’ which translates as brother in North Indian languages, can be a term of respect as well as endearance.

[8] Kutchis, largely a community of merchants and traders, are from the district of Kutch in the state of Gujarat.

*Deepa Punjani is the Editor of www.mumbaitheatreguide.com. She has an M.Phil in English Literature, and her M.Phil thesis revolves around the work of select Indian women in theatre in the context of feminism and gender representation on the Indian stage. She has acted on stage, has conducted theatre workshops and has designed theatre curricula. She has lectured on theatre in schools, colleges and at universities in Mumbai and has presented papers at various theatre conferences and seminars at home and abroad. In 2008, she formed the Indian national section of theatre critics, which is affiliated to the IATC. She currently represents this section.

Copyright © 2011 Deepa Punjani

Critical Stages/Scènes critiques e-ISSN: 2409-7411

This work is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution International License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.