Modern Scottish Theatre: Emerging from the Shadow of the Reformation

Mark Brown*

Abstract

Scottish theatre has, arguably, enjoyed its richest period over the last half-century. This paper will seek to explain Scotland’s relative lack of a historical theatre tradition and to explore the key elements in what the author proposes has been a “European modernist renaissance” on the national stage since 1969.

Keywords: Reformation, prohibition, European modernism, Havergal, Citizens Theatre

Scotland is unusual, if not necessarily unique, in being a nation whose finest dramatists are, arguably, alive and working today. The country’s theatre history is very different from that of England, its much larger, southern neighbour, to which it has been joined constitutionally for more than 300 years.[1] Scotland has, for example, no Shakespeare; its national bard is Robert Burns,[2] who was a poet, not a dramatist. Nor, for that matter, does it have an Aphra Behn,[3] a Thomas Otway[4] or a Richard Brinsley Sheridan.[5]

Liz Lochhead,[6] Scotland’s former Makar (national poet) and one of the nation’s leading playwrights, explains well the reason for the massive disparity between the theatre histories of the two countries:

[Scotland’s Calvinist Protestant] Reformation, early and thorough, stamped out all drama and dramatic writing for centuries. This means that the indigenous product seems to consist of Lyndsay’s 1540 Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaites[7] [sic]—and “ane satire” is definitely not enough. We have no Scottish Jacobean tragedies, no Scottish Restoration Comedies. Our greatest dramatist that never was, Burns, confined himself to the dramatic monologue purely in poetic form. . . . Holy Willie[8] and Tartuffe[9] may be brother archetypes, but only one had a full five-act play written about him.[10]

Lochhead is entirely correct to locate the central distinction between the theatre cultures of Scotland and England in the countries’ very different politico-religious histories. Whereas the English Reformation,[11] begun under King Henry VIII, was—broadly—tolerant of theatre (the only period of absolute national prohibition of live drama being during Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan republic, 1649–60), the Church of Scotland persecuted theatre so thoroughly that, it might be argued, the country did not begin to truly rebuild a national theatre scene until the early-twentieth century.[12] It is a peculiarity of Scottish history that in order to talk of the flourishing of the national theatre culture (which, I contend, has been particularly notable in the last 50 years), one must begin in the sixteenth century.

Although following the creation of the British state in 1707 Scottish theatre began to stutter back to life,[13] few experts would argue with the contention that Scotland’s theatrical renaissance truly begins in the early-twentieth century and sparks into life in the decades after the Second World War. In the early to mid-twentiethcentury, Scottish theatre witnessed the emergence of socialist playwrights such as Joe Corrie and C.P. Taylor and the humanist dramatist Ena Lamont Stewart. However, whilst the working-class orientation of these writers was radical in political terms (they might be considered the forebears of John McGrath and his socialist theatre company 7:84 Scotland, in the 1970s), artistically their work remained—broadly—in the tradition of English naturalism.

The creation of the influential Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh Festival Fringe (which, today, is the single biggest performing arts programme in the world) in 1947 had a profound impact upon the aesthetic orientation of Scottish theatre. Scottish audiences and, crucially, theatremakers were introduced belatedly to the artistic methods of European modernism. In time, this led to the establishment of the Traverse Theatre Club in Edinburgh,[14] the inaugural year (1963) of which included plays by such leading modernists as Jean-Paul Sartre, Alfred Jarry and Eugène Ionesco. However, it was the appointment of a young, Scottish theatre director by the name of Giles Havergal as artistic director of the Citizens Theatre in Glasgow in 1969 that truly brought modernist aesthetics into the heart of Scottish theatre culture.

Most of Havergal’s extraordinary, 34-year reign (1969–2003) at “the Citz” (as the Citizens Theatre is affectionately known in Scotland) was conducted as part of a directorial “triumvirate” with the acclaimed stage designer and director Philip Prowse and the late Robert David Macdonald,[15] who was an extremely accomplished translator, playwright and director. They brought to the Citz an aesthetic that encompassed the ideas and practices of continental European modernism, the artistic liberties of the European auteur director and the social and sexual radicalism unleashed by the political and countercultural movements of the 1960s. It was a measure of Havergal’s radicalism or Scottish society’s conservatism, according to one’s taste, that the Citizens’ outré, all-male production of Hamlet (in 1970) led to such an outcry in the press and society that the new director’s position was called into question. Thankfully, Havergal survived the backlash, enabling him, Prowse and MacDonald to establish the Citz as the finest theatre company in Scotland and, arguably, the most innovative and exciting in Britain. The leading English theatre critic Michael Coveney would later describe the company’s aesthetic as: “[a] theatre of visual delight and European orientation which [bore] no relationship whatsoever to the great upheavals in British theatre since the mid-1950s. . . . [They] renounced Scottishness, but renounced Englishness, too.”[16]

To get a sense of the European literary influence upon the Citizens’ programming one need only peruse the list of productions which includes works by: Artaud, Proust, Laclos, Anouilh, Brecht, Beckett, Genet, Büchner, Gogol, Goldoni, Lermontov, Beaumarchais, Balzac, Cocteau, Goethe, De Sade, Kraus, Hofmannsthal, Toller, Sartre, Offenbach, Hochhuth, Schiller, Kesselrig, Rojas, Musset, Tolstoy, Racine, Pirandello, Ibanez and Dumas.[17] For his part, Havergal was in no doubt that he and his co-directors were engaged very consciously in a project to distinguish their Glasgow theatre from the—typically naturalistic—English theatrical aesthetics that had become so prevalent throughout the U.K.:

In terms of the “Europeanness” of the work, Philip [Prowse] was always very determined that we wouldn’t become another “English company.” We were up in Glasgow (which was actually home to me, as it turned out), but not for them [Prowse and MacDonald], and we actually wanted to take advantage of being 400 miles away from London, [sic] and create our own style of theatre. I always summed it up by saying we didn’t care what the Royal Shakespeare Company was doing. We weren’t influenced by that. Whereas, I think, if you were in an English theatre at that time, you would have to have been. We simply weren’t connected to that whole organisation that was “English theatre.”[18]

The impact of the triumvirate on Scottish theatre over their 34 years is almost impossible to estimate. Leading playwright and artistic director David Greig comments:

I can’t think of any artistic director in Scotland who wouldn’t in some way want to emulate Giles [Havergal] or refer to him in relation to their own work . . . [Havergal] is the originator of a tradition, which is a gift . . . I could argue all sorts of different reasons why [Scottish theatre’s renaissance] happened in 1969, but maybe we were just bloody lucky that he was available at the time.[19]

Havergal retired from the Citizens in 2003. Whether his successor Jeremy Raison’s period (2003–10) succeeded in honouring the triumvirate’s legacy is a moot point. However, there is little debate about the success of the directorship of the current incumbent, Dominic Hill, whose distinctive style and classical repertoire are reminiscent, in many regards, of those established by Havergal.

Havergal’s directorship of the Citizens was, I contend, the major factor in the creation of the most artistically fruitful strand in the history of live drama in Scotland. Still in the process of emerging, even as late as 1969, from the darkness of Calvinist prohibition, the nation’s theatre, belatedly but wholeheartedly, embraced European modernist aesthetics, ultimately joining them with Scottish sensibilities and artistic achievements.

In Communicado: The Radicals on Tour

If the Citizens created a European modernist revolution in Scottish theatre in the 1970s, that revolution was transported around the country by new touring company Communicado in the 1980s. Established in Edinburgh in 1983, by Gerry Mulgrew, Alison Peebles and Rob Pickavance, the company combined the European inclinations of the Citz with a passion for Scottish texts (which did not feature strongly at Havergal’s theatre).

Mulgrew (who was familiar, from his training at Edinburgh’s Theatre Workshop in the 1970s, with the techniques of great European theatre masters such as Jerzy Grotowski and Jacques Lecoq) acknowledges a very definite debt to Havergal. However, he also identifies a Scottishness in his company (both in terms of the repertoire and the accents in which actors spoke) that distinguished Communicado from the Citz:

The Citizens . . . was a European theatre. It always slightly annoys me that Britain doesn’t see itself as part of Europe . . . We [in the British context] always speak about “the Europeans,” as if to keep them at arm’s length. We don’t really do that in Scotland, it’s more a southern English kind of thing . . . [However], in a sense, the Citizens wasn’t part of Scotland at all. There were very few Scottish actors who worked there. [The Citizens company] were seen as vagabonds or gypsies, exotic people doing exotic things. They all had English accents, but they were doing German and French plays.[20]

There were, of course, Scottish actors (most notably a young David Hayman) at the Citizens, but it is also true that Havergal’s theatre became a haven for English actors such as Rupert Everett and Glenda Jackson, whose European inclinations were not well catered for by the London stage. Even in the early-1980s, the general rule in Scotland was that Scottish accents were heard on stage only in Scottish plays. The classics were performed in “Received Pronunciation” (a supposedly “default” accent for the English language within the UK, which, in fact, was a bourgeois, southern English mode of speech). Communicado changed this state of affairs. In addition to Scottish work,[21] Mulgrew’s touring company gave a Scottish voice to work by such leading European writers as Lorca,[22] Büchner,[23] Schiller[24] and Gogol.[25]

Communicado theatre company can be credited with the dissemination throughout Scotland, from the early-1980s forward, of Havergal’s European modernist revolution and with giving that revolution a more distinctively Scottish voice. It should also be considered the trailblazer for a rich stream of touring and non-building based Scottish theatre companies and artists, all of whom shared and, in many cases, continue to share the European modernist inclinations of the Citizens and Communicado. These include such companies as: Suspect Culture, Vanishing Point, Grid Iron, children’s theatre companies Catherine Wheels and Wee Stories and children’s theatremakers Shona Reppe and Andy Manley.

The Golden Generation: The emergence of Scotland’s European Playwrights

Post-war Scotland had enjoyed a flourishing in playwriting; after Ena Lamont Stewart and C.P. Taylor came such writers as: Peter Arnott, John Binnie, John Byrne, Jo Clifford, Sue Glover, Chris Hannan, Iain Heggie, Jackie Kay, Liz Lochhead, John McGrath and Rona Munro.

Excellent though much of the output of these writers was, it tended, with some exceptions, to be written for Scottish audiences. There is nothing wrong with this, of course; creating Scottish plays for Scottish audiences was a crucial part of the process of the recovery of a national theatre culture. However, it wasn’t until the 1990s that a truly outward looking European playwriting came to the fore in Scotland.

The names David Greig (The Cosmonaut’s Last Message to the Woman he Once Loved in the Former Soviet Union, 1999), Zinnie Harris (Further Than the Furthest Thing, 2000), David Harrower (Knives in Hens, 1995) and Anthony Neilson (The Wonderful World of Dissocia, 2004) are well known throughout Europe and beyond. To them we should add Pamela Carter, a dramatist who has been active in Scottish theatre since the 1990s, including in important collaborations with Suspect Culture (the company of writer/director David Greig and director Graham Eatough, 1993–2009) and Untitled Projects (the company established by director/designer Stewart Laing in 1998). The work of these writers is characterised by a stylised, modernist and non-naturalistic aesthetic and, for the most part, a use of standard English (rather than Scots-English) which is easily translatable internationally. It has achieved for Scottish stage writing a previously unimagined stature and acclaim.

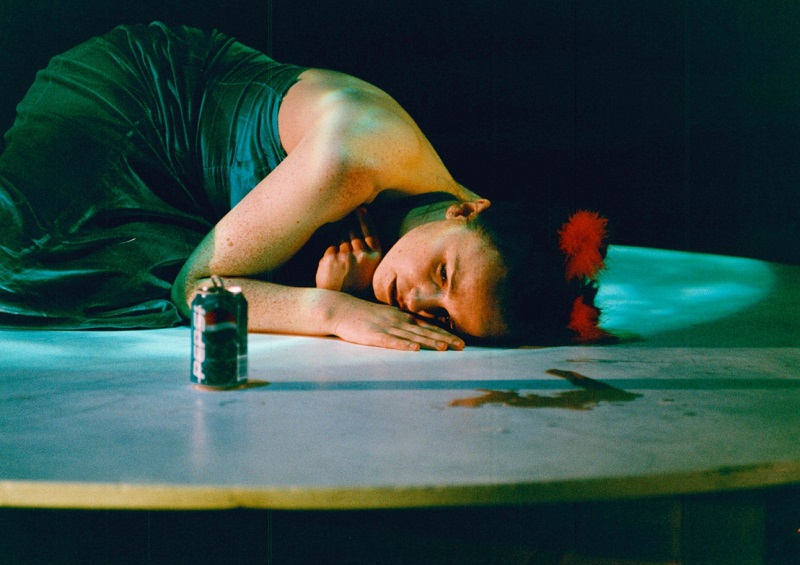

Video 1

A New National Theatre and Some New Players: Scottish Theatre Today

All of the above-mentioned playwrights who emerged in the 1990s (except Harrower who still writes for the screen) remain active in Scottish theatre; although Neilson has long been based in London, he often premieres his work in Scotland. Greig was appointed artistic director of Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum Theatre in 2015, whilst Harris has become a fine stage director (with productions including Caryl Churchill’s A Number, 2017, and her own adaptation of John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, 2019). In the new millennium, they have been joined by a panoply of theatremakers who have created notable new work for the Scottish stage, including: Henry Adam, Cora Bissett, Rob Drummond, Nic Green, Kieran Hurley, David Ireland, DC Jackson, David Leddy, Isobel McArthur, Martin McCormick, Johnny McKnight, Gary McNair, Adura Onashile, Morna Pearson, Stef Smith and Meghan Tyler.

The output of these dramatists has been incredibly diverse, ranging from self-performed solo works (such as Drummond’s Bullet Catch, 2012, and Hurley’s Beats, 2012), to more conventionally scripted plays (perhaps most notably David Ireland’s Ulster American, 2018) and a celebrated feminist “participatory performance work” (Nic Green’s Trilogy,2009).

The most significant post-millennial development in Scottish live drama has been the establishment of the National Theatre of Scotland by the Scottish parliament in 2006. The overwhelming vote of the Scottish people for a Scottish parliament with tax varying powers in the devolution referendum in 1997 led to the founding of the country’s first democratic parliament in 1999. With devolution has come an increased sense of cultural self-confidence in Scotland. The decision to create a National Theatre of Scotland (NTS) was a response to an increasingly strong demand from within the theatre community and the theatre audience. The NTS was established as a company without a theatre building of its own, operating out of administrative offices in Glasgow. It defined itself as a “theatre without walls” (a model that has become influential internationally, particularly for small nations seeking a national theatre of their own).

Significantly, the first artistic director of the NTS was not a Scot but an Englishwoman who had excellent connections with Scottish theatre and a sound understanding of Scotland’s theatre ecology. Vicky Featherstone (who held the post from 2006 until 2013, when she was appointed artistic director of the Royal Court Theatre in London) successfully mapped the NTS onto the existing theatrical landscape. The company’s diverse, forward looking output covered small scale productions in some of Scotland’s many and diverse rural communities, such as those in the Highlands and Islands and in the Lowlands, as well as large scale classics and new work from different traditions within Scottish theatre.

Video 2

The company’s most critically acclaimed production thus far came in its first months. Black Watch (which premiered at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2006) is what I term a “play production,” in the sense that the work, as it has been experienced by audiences, is not a stand-alone play by its writer Gregory Burke but the culmination of both the writing and the auteur directorship of John Tiffany (the NTS’s associate director for new work between 2006 and 2013). Based upon interviews that Burke conducted with former members of the Scottish regiment of the British Army, known as the Black Watch, who had served in occupied Iraq in 2004, the piece was a powerful, moving, often unexpectedly humorous twist on the (then as now) fashionable verbatim drama genre. Burke’s imaginative interpretation of the interview material, combined with Tiffany’s eye for the theatrical image, created a production that has enjoyed extraordinary success in Scotland, throughout the U.K. and abroad, mainly in Anglophone countries with large Scottish diasporas such as Canada, the United States and Australia.

The NTS also took due notice of the European modernist strand in Scottish theatre that has been the primary subject of this paper. This has included Aalst (an English-language work from 2007, based upon a Flemish-language play by Belgian theatre company Victoria and directed by Pol Heyvaert from the Flemish group) and collaborations with the leading Scottish auteur director Stewart Laing (most notably Paul Bright’s Confessions of a Justified Sinner in 2013).

Video 3

There have been two NTS artistic directors since Featherstone’s departure (namely, Laurie Sansom, 2013–16, and Jackie Wylie, who took over in 2017). The 2020 NTS programme indicates a continuity with Featherstone’s philosophy of diverse and forward-looking programming, albeit that the new work also reflects Wylie’s background in non-conventional performance in her many years as a programmer of performance art and devised theatre at Glasgow’s now defunct arts venue The Arches.

The work in 2020 will encompass new approaches to established classics (an adaptation of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People by writer Kieran Hurley and director Finn den Hertog and a—no doubt innovative—take on Shakespeare’s Hamlet by Stewart Laing), a revival of a celebrated Scottish adaptation (Liz Lochhead’s Scots-English version of Euripides’s Medea) and a potentially powerful multi-media piece about the history of Scottish involvement in the African slave trade (Ghosts by Adura Onashile).

Conclusion

This paper has sought to put what I consider to be the most aesthetically significant elements in the Scottish theatrical renaissance within a historic context. Its emphasis on the European modernist strand in the national theatre culture is entirely intentional and, indeed, unapologetic. That said, this account cannot be, nor is it intended to be, exhaustive. There are numerous other important aspects of Scotland’s modern theatre culture that are worthy of consideration, including the popular, political theatre tradition of agitational propagandist companies such as John McGrath’s[26] 7:84 Scotland (1973–2008) and Wildcat theatre company (1978–2007).

Also, as Scotland-based theatre critic Mark Fisher wrote recently in this journal, respect is due to the “international programming [of Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre], especially in the 1980s and early 1990s . . . [including] work presented in the era of directors Steve Unwin and Jenny Killick, such as Losing Venice by Jo Clifford in 1985 and Manfred Karge’s Man to Man, starring Tilda Swinton, in 1987.”[27] Further to that, one should not overlook the immense influence of Glasgow’s successful year as European Capital of Culture (1990).

These elements and more join those explored in this paper in creating a vibrant theatre culture in Scotland, and one that has emerged over the last century from a harsh history of religious prohibition. Let’s give the final word to Matthew Lenton, artistic director of Vanishing Point theatre company, who describes the recent history and current landscape of Scottish theatre very well:

As [an English theatremaker] influenced by European theatre and little interested in the English tradition of playwriting, Glasgow and Scotland felt like a great place to be. It still is . . . [Scottish theatre is] outward-looking, internationalist, uninterested in cultural museum pieces and focused on the new . . . [Its modern achievements are exemplified by the] Havergal, Prowse and MacDonald era at the Citizens theatre, where classic European and contemporary plays came magnificently to life and made the Citz world famous. Tramway [arts venue in Glasgow] was the epicentre of internationalism. The legacy of Glasgow’s year as European Capital of Culture in 1990—with the programming of monumental international artists such as Peter Brook and Robert Lepage and Scottish artists such as Gerry Mulgrew—began to influence a whole generation of theatre practitioners. There was the illicit, exciting experimentalism of the Arches [sic] and the CCA [Centre for Contemporary Arts in Glasgow]

Things have been lost and gained. Tramway is no longer the international powerhouse it once was; the Arches has gone. But there is an innovative National Theatre of Scotland, which was conceived to take its shows to people all across its nation, rather than sit in the centre of its capital to be enjoyed by the few. There is a supremely confident Citz [under artistic director Dominic Hill], which offers reinterpretations of classical plays and populist new work, and brilliant young artists, from all backgrounds, working wherever they can.[28]

Endnotes

[1]The Treaty of Union, in which the Scottish parliament in Edinburgh was dissolved and Scotland was joined with England (which already incorporated Wales) in the new state of Great Britain to be governed from London, was enacted in 1707 (following the passage of Acts of Parliament in the legislatures of both Scotland and England).

[2]Robert Burns (1759–96), often known as the “Ploughman Poet” hailed from the southern Scottish rural county of Ayrshire. His poems and lyrics are written both in the Scots language and in English inflected with Scots. Considered a pioneer of the Romantic movement, Burns’s life and poetry became a source of inspiration for future socialists and other left-wing radicals.

[3]Restoration dramatist and author Behn (1640–89) was a trailblazer in English theatre, being one of the first women to become a professional playwright. A beneficiary of the reopening of the English theatres under Charles II, her plays include The Forc’d Marriage (1670) and The Rover (1677).

[4]Although his life was tragically impoverished and short, Otway (1652–85) was one of the outstanding dramatists of the Restoration period. His most notable plays include The Orphan (1680) and his masterwork, Venice Preserv’d (1682).

[5]An Anglo-Irishman, Sheridan (1751–1816) was the author of notable comedies such as The Rivals (1775) and The School for Scandal (1777).

[6]Born in 1947, Lochhead was Scotland’s Makar (national poet) between the years of 2011 and 2016. In addition to her considerable poetic output, she is the author of many plays, including original works such as Mary Queen of Scots Got Her Head Chopped Off (1987), Perfect Days (1998) and Thon Man Molière (2016), and adaptations of Greek classics, such as Euripides’s Medea (2000), and plays by Molière, including Tartuffe (1986) and The Misanthrope, retitled Miseryguts, (2002).

[7]Sir David Lyndsay’s (1490–1555) social and political satire Ane Pleasant Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis (1540) is considered a classic of Scotland’s comparatively scant theatrical history. Revived from time to time in the modern era, it was most recently performed in 2013 at Linlithgow Palace by the Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project Staging and Representing the Scottish Renaissance Court.

[8]The hypocritical religious moralist who is the subject of Robert Burns’s 1785 poem “Holy Willie’s Prayer.”

[9]The charlatan priest who is the subject of Molière’s 1664 play Tartuffe.

[10]Quotation from Lochhead’s introduction to Educating Agnes, her Scots-English adaptation of Molière’s The School for Wives (Nick Hern Books, 2008), p. 7.

[11]England’s Reformation (1527–90), despite its ferocious anti-Catholicism, created a notably neo-Catholic Church of England which was, and remains, very distinct from the Lutheran and Calvinist churches of Protestant Europe, including the Calvinist Church of Scotland.

[12]J.M. Barrie (1860–1937), the author of Peter Pan, might be considered the finest Scottish playwright to emerge between the Reformation and the twentieth century. However, his success was achieved not in Scotland but in London.

[13]Readers who are interested in the slow, historical revival of live drama in Scotland are recommended to read A History of Scottish Theatre, edited by Bill Findlay (Edinburgh UP, 1998).

[14]Which would become the Traverse Theatre, Scotland’s self-defined “new writing theatre.”

[15]MacDonald died in 2004.

[16]Michael Coveney, The Citz: 21 Years of the Glasgow Citizens Theatre (Nick Hern Books, 1990), p. 4.

[17]From the 1969–90 production list in Coveney, pp. 85–295.

[18]Havergal, from interview with Mark Brown (Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, London, 14 Nov. 2012).

[19]David Greig, from interview with Mark Brown (Greig’s office, central Edinburgh, 13 Nov. 2015).

[20]Gerry Mulgrew, from interview with Mark Brown (Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh, 18 Feb. 2014).

[21]Such as a stage adaptation of Scottish author George Douglas Brown’s 1901 novel The House with the Green Shutters (1983), the premiere of Liz Lochhead’s play Mary Queen of Scots Got Her Head Chopped Off (1987) and a staging of Robert Burns’s great poem Tam o’ Shanter (2009).

[22]Blood Wedding (1988).

[23]Woyzeck (2001).

[24]Mary Stuart (2006).

[25]The Government Inspector (2011).

[26]1935–2002.

[27]From Fisher’s review of Modernism and Scottish Theatre Since 1969 by Mark Brown, Critical Stages no. 19: critical-stages.org/19/modernism-and-scottish-theatre-since-1969 (accessed 20 Dec. 2019).

[28]From Lenton’s essay “Scottish Independence? In Theatre, It’s Long-established,” The Guardian, 25 Mar. 2016 (accessed 20 Dec. 2019).

*Mark Brown is theatre critic of the Scottish national newspapers The Herald on Sunday and the Sunday National, and Scottish critic of the U.K. national title the Daily Telegraph. He is a regular teacher at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and other universities and the author of the book Modernism and Scottish Theatre since 1969: A Revolution on Stage.

Copyright © 2019 Mark Brown

Critical Stages/Scènes critiques e-ISSN: 2409-7411

This work is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution International License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Pingback: Close to the very best of Scottish theatre | Leaf Collecting